Processes the Input Elements Continuously Producing Output One Element at a Time

Part 1: Symmetric Ciphers¶

Chapter 2. Classical Encryption Techniques¶

Definitions of Terms *¶

- Plaintext: original message

- Ciphertext: coded message

- Enciphering or encryption: the process of converting from plaintext to ciphertext

- Deciphering or decryption: the process of restoring the plaintext from the ciphertext

The many schemes used for encryption constitute the area of study known as cryptography. Such a scheme is known as a cryptographic system (cryptosystem) or a cipher. Techniques used for deciphering a message without any knowledge of the enciphering details fall into the area of cryptanalysis. Cryptanalysis is what the layperson calls "breaking the code". The areas of cryptography and cryptanalysis together are called cryptology.

Symmetric Cipher Model¶

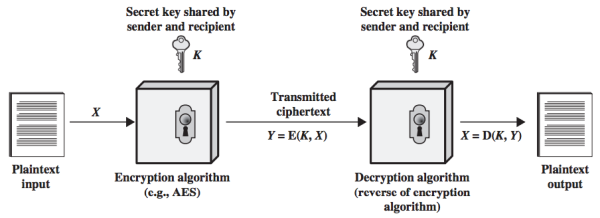

A symmetric encryption scheme has five ingredients (as shown in the following figure):

- Plaintext: This is the original intelligible message or data that is fed into the algorithm as input.

- Encryption algorithm: The encryption algorithm performs various substitutions and transformations on the plaintext.

- Secret key: The secret key is also input to the encryption algorithm. The key is a value independent of the plaintext and of the algorithm. The algorithm will produce a different output depending on the specific key being used at the time. The exact substitutions and transformations performed by the algorithm depend on the key.

- Ciphertext: This is the scrambled (unintelligible) message produced as output.

- It depends on the plaintext and the secret key. For a given message, two different keys will produce two different ciphertexts.

- Decryption algorithm: This is essentially the encryption algorithm run in reverse. It takes the ciphertext and the secret key and produces the original plaintext.

Encryption Requirements *¶

There are two requirements for secure use of conventional encryption:

- The encryption algorithm must be strong.

- At a minimum, an opponent who knows the algorithm and has access to one or more ciphertexts would be unable to decipher the ciphertext or figure out the key.

- In a stronger form, the opponent should be unable to decrypt ciphertexts or discover the key even if he or she has a number of ciphertexts together with the plaintext for each ciphertext.

- Sender and receiver must have obtained copies of the secret key in a secure fashion and must keep the key secure. If someone can discover the key and knows the algorithm, all communication using this key is readable.

Why not keep the encryption algorithm secret? *¶

We assume that it is impractical to decrypt a message on the basis of the ciphertext plus knowledge of the encryption/decryption algorithm. This means we do not need to keep the algorithm secret; we need to keep only the key secret. This feature of symmetric encryption makes low-cost chip implementations of data encryption algorithms widely available and incorporated into a number of products. With the use of symmetric encryption, the principal security problem is maintaining the secrecy of the key.

Model of Symmetric Cryptosystem *¶

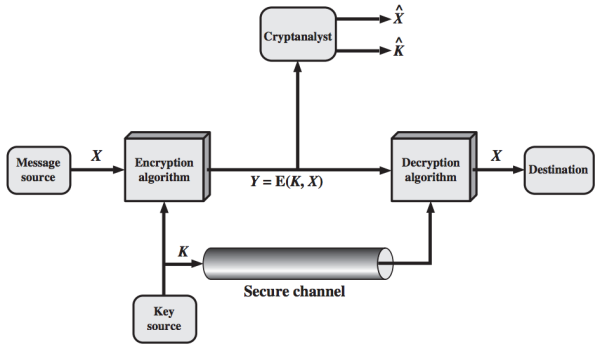

The essential elements of a symmetric encryption scheme is described in the following figure:

- A source produces a message in plaintext, .

- A key of the form is generated.

- If the key is generated at the message source, then it must also be provided to the destination by means of some secure channel.

- Alternatively, a third party could generate the key and securely deliver it to both source and destination.

- The ciphertext is produced by the encryption algorithm with the message X and the encryption key K as input.

The encryption process is:

This notation indicates that Y is produced by using encryption algorithm E as a function of the plaintext X, with the specific function determined by the value of the key K.

The intended receiver with the key is able to invert the transformation:

An opponent, observing Y but not having access to K or X, may attempt to recover X or K or both. It is assumed that the opponent knows the encryption (E) and decryption (D) algorithms. The opponent may do one of the following:

- Recover X by generating a plaintext estimate , if the opponent is interested in only this particular message.

- Recover K by generating an estimate , if the opponent is interested in being able to read future messages.

Cryptography¶

Cryptographic systems are characterized along three independent dimensions:

-

Type of operations for transforming plaintext to ciphertext. All encryption algorithms are based on two general principles:

- Substitution: each element in the plaintext (bit, letter, group of bits or letters) is mapped into another element,

- Transposition: elements in the plaintext are rearranged.

The fundamental requirement is that no information be lost (all operations are reversible). Product systems involve multiple stages of substitutions and transpositions.

-

Number of keys used.

- If both sender and receiver use the same key, the system is referred to as symmetric, single-key, secret-key, or conventional encryption.

- If the sender and receiver use different keys, the system is referred to as asymmetric, two-key, or public-key encryption.

- How the plaintext is processed.

- A block cipher processes the input one block of elements at a time, producing an output block for each input block.

- A stream cipher processes the input elements continuously, producing output one element at a time, as it goes along.

Cryptanalysis and Brute-Force Attack¶

The objective of attacking an encryption system is to recover the key in use rather than simply to recover the plaintext of a single ciphertext. There are two general approaches to attacking a conventional encryption scheme:

- Cryptanalysis (cryptanalytic attacks): This attack relies on the nature of the algorithm plus some knowledge of the general characteristics of the plaintext or some sample plaintext–ciphertext pairs. It exploits the characteristics of the algorithm to attempt to deduce a specific plaintext or to deduce the key being used.

- Brute-force attack: The attacker tries every possible key on a piece of ciphertext until an intelligible translation into plaintext is obtained. On average, half of all possible keys must be tried to achieve success.

If either type of attack succeeds in deducing the key, then future and past messages encrypted with that key are compromised.

Cryptanalytic attacks *¶

The following table summarizes the various types of cryptanalytic attacks based on the amount of information known to the cryptanalyst.

| Type of Attack | Known to Cryptanalyst |

|---|---|

| Ciphertext Only |

|

| Known Plaintext |

|

| Chosen Plaintext |

|

| Chosen Ciphertext |

|

| Chosen Text | Combination of "Chosen Plaintext" and "Chosen Ciphertext" |

[p32]

In general, we can assume that the opponent does know the algorithm used for encryption. If the key space is very large, the brute-force approach of trying all possible keys, which is one possible attack, becomes impractical. Thus, the opponent must anaylyze the ciphertext itself, applying various statistical tests to it. To use this approach, the opponent must have some general idea of the type of plaintext that is concealed.

Ciphertext-only attack *¶

The ciphertext-only attack is the easiest to defend against because the opponent has the least amount of information to work with.

Known-plaintext attack *¶

In many cases, the analyst has more information than ciphertext only:

- The analyst may be able to capture one or more plaintext messages and their encryptions.

- The analyst may know that certain plaintext patterns will appear in a message.

For example, a file that is encoded in the Postscript format always begins with the same pattern, or there may be a standardized header or banner to an electronic funds transfer message. All these are examples of known plaintext. With this knowledge, the analyst may be able to deduce the key on the basis of the way in which the known plaintext is transformed. This is known as the known-plaintext attack.

Probable-word attack *¶

The probable-word attack is closely related to the known-plaintext attack. If the opponent is working with the encryption of some general prose message, he or she may have little knowledge of what is in the message. However, if the opponent is after some very specific information, then parts of the message may be known.

For example:

- If an entire accounting file is being transmitted, the opponent may know the placement of certain key words in the header of the file.

- The source code for a program developed by a company might include a copyright statement in some standardized position.

Chosen-plaintext attack *¶

If the analyst is able to get the source system to insert into the system a message chosen by the analyst, then a chosen-plaintext attack is possible. An example of this strategy is differential cryptanalysis, explored in Chapter 3. In general, if the analyst is able to choose the messages to encrypt, the analyst may deliberately pick patterns that can be expected to reveal the structure of the key.

The other two types of attack: chosen ciphertext and chosen text, are less commonly employed as cryptanalytic techniques but are nevertheless possible avenues of attack.

Generally, an encryption algorithm is designed to withstand a known-plaintext attack; only weak algorithms fail to withstand a ciphertext-only attack.

Unconditionally secure and computationally secure *¶

An encryption scheme is unconditionally secure if the ciphertext generated by the scheme does not contain enough information to determine uniquely the corresponding plaintext, no matter how much ciphertext is available. That is, no matter how much time an opponent has, it is impossible for him or her to decrypt the ciphertext simply because the required information is not there.

With the exception of a scheme known as the one-time pad (described later in this chapter), there is no encryption algorithm that is unconditionally secure. Therefore, an encryption algorithm should meet one or both of the following criteria:

- The cost of breaking the cipher exceeds the value of the encrypted information.

- The time required to break the cipher exceeds the useful lifetime of the information.

An encryption scheme is said to be computationally secure if either of the foregoing two criteria are met. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to estimate the amount of effort required to cryptanalyze ciphertext successfully.

All forms of cryptanalysis for symmetric encryption schemes are designed to exploit the fact that traces of structure or pattern in the plaintext may survive encryption and be discernible in the ciphertext. Cryptanalysis for public-key schemes proceeds from a fundamentally different premise: the mathematical properties of the pair of keys may make it possible for one of the two keys to be deduced from the other.

Brute-force attack *¶

A brute-force attack involves trying every possible key until an intelligible translation of the ciphertext into plaintext is obtained.

On average, half of all possible keys must be tried to achieve success. A brute-force attack is more than simply running through all possible keys. Unless known plaintext is provided, the analyst must be able to recognize plaintext as plaintext:

- If the message is just plain text in English, then the result pops out easily, although the task of recognizing English would have to be automated.

- If the text message has been compressed before encryption, then recognition is more difficult.

- If the message is some more general type of data, such as a numerical file, and this has been compressed, the problem becomes even more difficult to automate.

Thus, to supplement the brute-force approach, some degree of knowledge about the expected plaintext is needed, and some means of automatically distinguishing plaintext from garble is also needed.

poundsdowerent1968.blogspot.com

Source: https://notes.shichao.io/cnspp/ch2/

0 Response to "Processes the Input Elements Continuously Producing Output One Element at a Time"

Post a Comment